Adriana Huerta and the ERC Citizenship Ambassador Program: A loan “with a catch” builds a program

Explore More

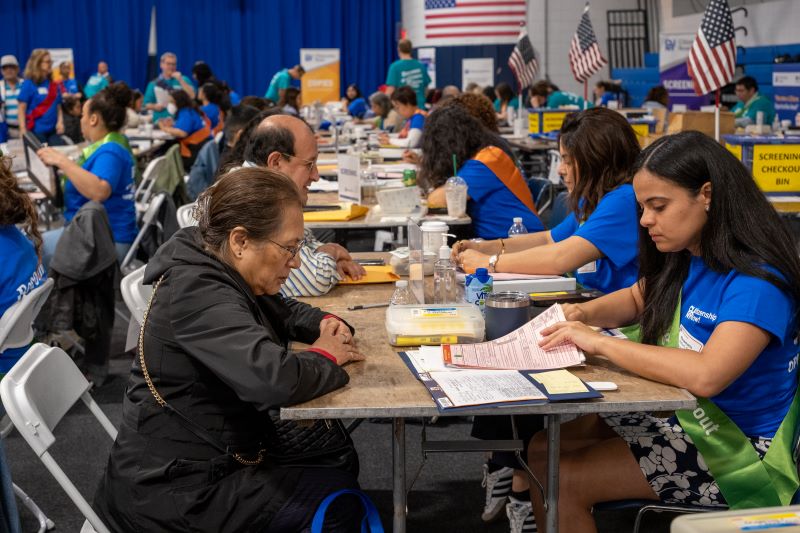

After graduates of the Employee Rights Center’s citizenship program in San Diego take their oath of citizenship, they frequently return to the ERC to pose for photos—holding high their new US citizenship certificates. Celebrating by their side, in photo after photo, is Adriana Huerta, the Center’s Community Health Educator. Huerta is a cheerleader for naturalization who has developed a “Citizenship Ambassadors” program—encouraging her clients to tap into their personal networks, share their own stories, and educate people about the Center’s support system for aspiring citizens.

Huerta herself became a citizen through ERC’s program, and was soon helping

others who also hoped to naturalize. Huerta originally joined ERC to manage

workers’ compensation and disability cases as a health educator, but she soon

recognized that workers would have better opportunities if they became citizens.

Huerta knows first hand how daunting the application process can be. She was

born in Mexico, attended college in the U.S. and married a U.S. citizen. After

she received her green card, it took more than a decade for her to fill out an

application for citizenship. “I was afraid of the process,” says Huerta.

“It doesn’t matter how educated you are, the process itself is intimidating.”

Alor Calderon, ERC Director, appreciated Huerta’s connection with clients

and eventually trained her to manage ERC’s immigration and naturalization

program. In their office they now process 300 applications a year.

and Adriana (right) (Photos courtesy of ERC)

As the citizenship program grew Huerta wanted to find a way to reassure applicants on a personal level and ease their fears. At the same time, ERC had many clients who were so grateful for the assistance they received that they wanted to do something to give back. With that synergy, Huerta’s citizenship ambassador program took shape as she found clients who were eager to “pay it forward.” At any given time, Huerta has 25 to 40 ambassadors, ready to reach out and encourage a new client to begin the process. Hugo Carreon is one of Huerta’s ambassadors who isn’t shy about promoting ERC’s services. “You just put out the word,” says Carreon, “and let people know all the benefits of the program. I give people flyers. I pass along the phone number and tell them who to talk to. I let them know that if they have any doubts or any questions just call me and I will answer, and they can decide whether this is for them or not.”

(Photo courtesy of Hugo Carreon)

Promoting citizenship, recruiting clients and boosting the confidence of the

applicants is only part of the equation. The ERC also helps applicants pay

for the steep application fees. They offer a no-interest loan program if

people don’t have the money up front and don’t qualify for the USCIS

fee waiver. The loan program is called ERC 25 and it sets aside $25,000 from

ERC’s own internal budget as a loan fund. As people repay their loans, the

money goes back into the fund and becomes available to a new applicant. That

sealed the deal for Carreon, a professional ballet dancer, who moved from

Mexico City to San Diego to dance. He had his green card and he wanted to

become a citizen but “it was a matter of the money. Lots of money,” he said. “I

got a no interest loan,” he said, “and I was able to take my time paying it

back. It’s been amazing. They don’t charge you for the advice, they help you

fill out the paperwork, and you can take your time paying it back.”

(Courtesy: California Ballet)

But there’s a catch, says Huerta: if an applicant is approved for a no interest loan, in additional to paying the money back, they must agree to become a citizenship ambassador or to help with fundraisers. “The only formal agreement we have is that the person signs a model agreement to become an ambassador to help spread the word about the loan program, to

organize or provide direct assistance to some of the people who want to become citizens, and to help them with fundraisers in the future.” Clients also promise to refer people to the program and to bring their certificate back and

allow the organization to take a picture and share their story.

Carreon is a natural ambassador.

Whenever he visits one of San Diego’s street taco shops for lunch he asks if

the workers have their green cards yet. “Most people have it, but I will then

ask, ‘Are you a citizen yet?’” That’s when the information card comes out. “I

tell them here’s the card, here’s the number. You get this done now. We must

vote.” Carreon talks with his friends and ballet colleagues as well,

encouraging them to apply to naturalize, to become more civically engaged, or

to attend a fundraising dance party. He says ERC has been “life saving” for

him. In addition to help with applying for citizenship and paying the fees, ERC

is now helping him set up his own ballet company. “They opened the door to a

whole new world of possibilities, really,” he said. “The success of our program

is the trust-based personal relationship we develop with people,” says Huerta.

“People need to be treated with respect and dignity and patience and they to

understand that their information is secure. And they get a really human, warm,

embrace.”