Josephine Kalondji: A Citizen of Somewhere!

Explore more

I was born in Congo, but my family fled from Congo when I

was 10 months old. During that time, there was a lot of political corruption

and tribal warfare. My dad was a teacher and we wanted to escape the lack of

education, health, instability, and the inability to access basic human needs. When

we were fleeing Congo, my family was separated. My mom, my second oldest

brother, and I made it to Mozambique. But my grandmother, my dad, and my oldest

brother were caught and sent back. We were reunited a year later. I lived in

the refugee camp in Mozambique until I was 12 years old. There were five of us,

my two older brothers and a younger brother and sister who were born in the

camp.

Since my dad was a teacher, he always valued education. I

remember I was hungry sometimes and we would sell our school materials for

food. Even though there are organizations that give refugees food, it’s never

enough. My mom used to grow most of our food. Every morning we would wake up

and go water the tomatoes or whatever we were growing.

My parents would always talk about coming to the United

States. We were fortunate to be admitted in 2013. We came to Dallas, Texas. Everything

was new from the culture to the language. The only two languages that I knew

were Portuguese and Swahili. I had to learn English in school. I repeated

seventh grade because of the language barrier.

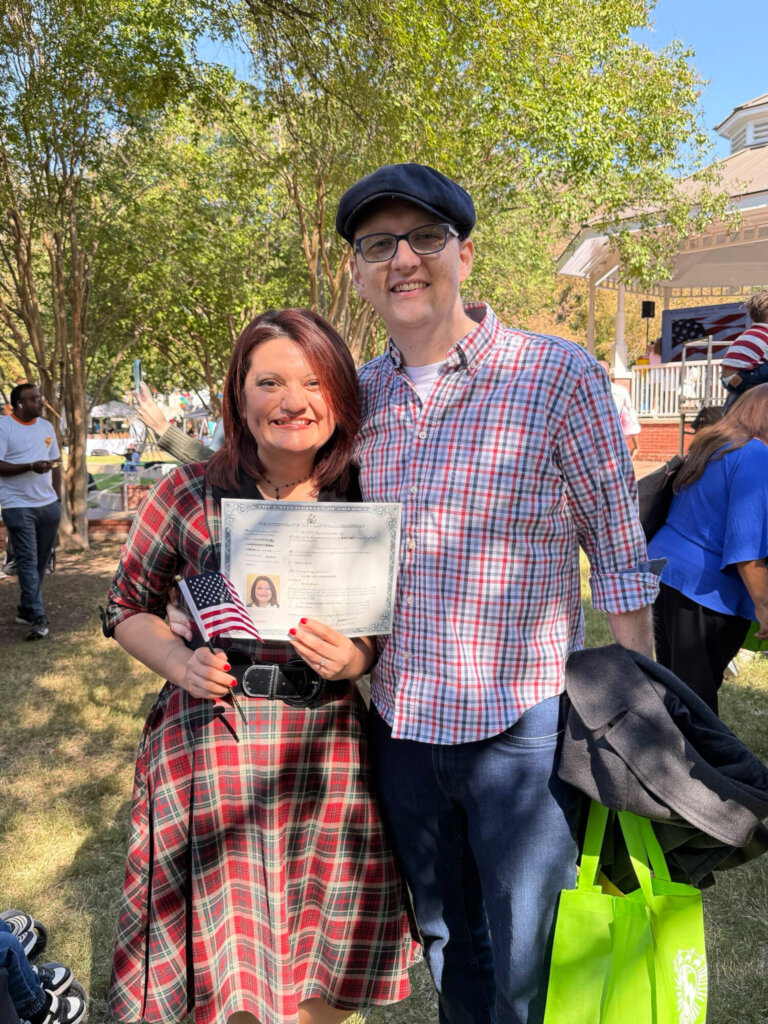

(Photo courtesy of Josephine Kalondji)

My dad is now a chef at Seasons 52. He has worked there for 7 years, ever since we got here. My parents decided to become citizens, but I turned 18 two months after my dad put his application in, which meant that I had to apply on my own. My dad actually asked me whether I wanted to become a U.S. citizen, which was very unusual because as a person who grew up in Africa, your parents make the decisions for you. They don’t ask you. But he reminded us that we came a long way from having a home, to being an immigrant elsewhere, and now we have the opportunity to belong somewhere. My dad told us that he was going to take that step forward and whoever wanted to join him, we should let him know.

I applied for my U.S. citizenship last year. Being an American citizen was something that I was looking forward to. As a college student at Holy Cross, I applied in Massachusetts with the help of International Rescue Committee (IRC) in Dallas, Texas. IRC helped my parents and me fill in the information for our naturalization applications. I did not know anyone in Massachusetts, so I had to go to my own appointments related to the naturalization process, and I had to keep up with everything. But every time I needed anything, I could call IRC and they would tell me exactly what to do.

I was very nervous before the citizenship test because I

studied for so many questions and I knew that I needed to pass six. I studied

10 questions every single day until I knew all the answers. I was also

fortunate because I volunteered at an ESL program and somebody else from there

was also applying for citizenship. I helped them with English and then we would

help one another study the questions. Still, I worried—what if they ask me

something that I did not put my attention to? At the test I was sitting next to

someone who didn’t speak as much English as I did. They asked her hard

questions. But then they asked me easy questions such as, who’s the president

of the United States? What is the party of the president of the United States?

Now I know what to expect, and I know how to help somebody else who might be

going through the same process.

Fortunately, my oath ceremony was in February, before the pandemic sent me home from college. I went by myself. Even though everything was my responsibility, I could rely on Holy Cross to help me. They provided transportation from Worcester, MA to Lawrence, MA. The driver’s name was Anthony, but he goes by Tony. Every single USCIS appointment that I had was at least an hour away. Tony would drive me there, wait for me, and then take me back. He took me to all three appointments. Sometimes he would offer to buy food for me, just knowing how long these appointments were.

Tony was born in the United States, but his parents were

Portuguese and Italian. Even though he didn’t have to go through what I was

going through, he was empathetic because he knew what his parents went through.

On the drive he would talk about the benefits of being American. He would

comfort me and tell me, “It’s worth it, you can do this!” And “I’m here next to

you!” Just watching him be excited for me was very, very valuable. Tony also

offered to be present at my ceremony, which was very meaningful to me because I

learned so much from him.

At the ceremony there were at least a thousand people in the auditorium. I was there by myself, but I think mentally I was there with my whole community at Holy Cross, and at home as well. It was very beautiful because we had different people from different places. And I had the opportunity of meeting people that I would’ve never met otherwise. It was so huge I couldn’t see Tony. But he clapped for me. And after he said, “Oh you have made it now.” And he joked that it was a great thing because he wouldn’t have to take me to these long appointments. I will never forget him—never.

I voted in the election. I was a little nervous. I thought the line would be long, but it wasn’t. I thought they would ask me many questions, but it was straightforward. Everybody there was very nice, very inclusive. My two older brothers and I often sit down and reflect. We ask each other, who would we have been if we were back in Africa? And even though we don’t know, we look at our friends there, and see the difficult life that they have, and it’s scary to think that would have been our reality as well. I recognize the privilege that I now have. I’ve earned my way to becoming like everybody in the United States. For the past seven years, as a kid, I had the title of refugee; it de-humanizes you. I feel like I belong somewhere now. I have the same rights. I’m an American citizen now—a citizen of somewhere! I feel like I learned so much from the experience of becoming a citizen. It was a long process, but I know I was very fortunate. It took me six months, and it took my parents almost two years. It can seem that it’s very expensive, but there are people who want to help. I was helped by IRC to get a fee waiver. There are so many people who want to help, it’s just a matter of you allowing them to help you. There are other people who will come after me. My goal is to use my experience to help other refugee children gain an education and have their basic needs met. My life was made better by other people, so now it’s my turn to make somebody else’s life better.