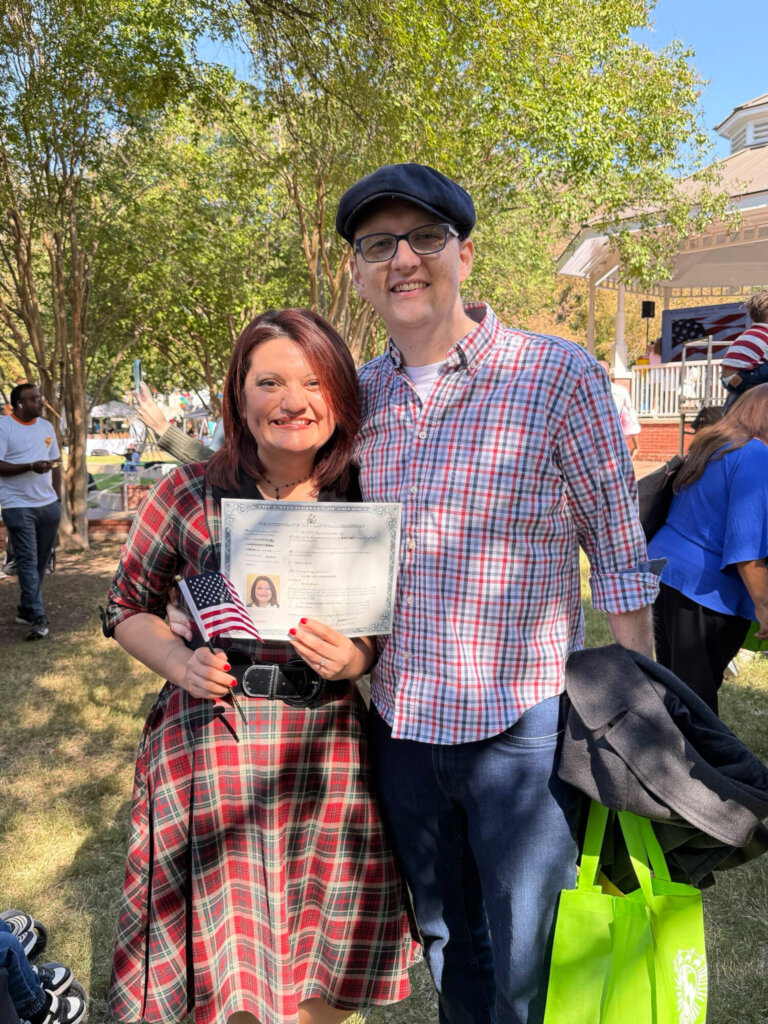

Citizenship and Naturalization Are Under Attack (The Hill)

April 16, 2025

The Trump administration is wasting no time making American citizenship harder to access and easier to deny. Just weeks into…

News and Insights

The latest from the New Americans Campaign, naturalization and citizenship news, and stories from new Americans

April 16, 2025

April 21, 2025

April 3, 2025

February 6, 2025